MAMMAL NAMES | Alien Invasion!:

- Stephen Daly

- Jun 30, 2017

- 9 min read

Updated: Dec 15, 2021

How the Scientific Name of the Grey Squirrel Reveals an Epic Invasion of Ireland

Ireland’s history is often told as a story of invasions, of clashing swords and roaring cannon, of natives expropriated by more powerful invaders followed by a long struggle to reclaim ancestral lands. But, of course, the tale we tell is a human one, concerned mainly with the impact of the arrival of foreign soldiers and colonisers on the native people of Ireland. However, there is another story of natives and invaders which runs parallel to this human story, and is intimately interwoven with it: that of the many species of animals from foreign lands that have invaded Ireland with the aid of humans and the impact these aliens have had on native species. One of the best-documented episodes in this epic clash between natives and invaders is the long-running struggle between Ireland’s native red squirrel and the invasive grey squirrel, which has raged for over a century. And the scientific names of both these species serve as a perfect launching point to understand the origins of this epic struggle and the triumphs and failures on both sides.

Before we get to these scientific names, though, we must first be introduced to the two species involved, the red squirrel and the grey squirrel. As their English names suggest, these two squirrel species are named on the basis of their coat colour, and the Irish names, iora rua and iora glas, mean the same thing, ‘red squirrel’ and ‘grey squirrel’, respectively.

However, these two squirrels are often not as different in colour as these names might suggest, and their coat colours can overlap to some degree. For instance, the red squirrel is actually generally a brownish colour and can even be greyish brown, while the grey squirrel is generally some kind of brownish grey.

It would still be hard to confuse the two in most instances, though, as there are still marked differences between them. The grey squirrel, for example, is a good deal larger than the red squirrel, being about 48 centimetres in length and roughly 400–700 grams in weight, while the red is only around 40 centimetres long and 250–400 grams in weight. But even in cases where identification by size may be difficult – in the case of juveniles, say – the red can still be easily identified as the tops of its ears have funny little tufts of hair jutting upwards making them look a bit like the ears on Batman’s cowl, a feature never seen in greys.

As different as they are in some ways, though, the reds and greys share that unmistakable feature that characterises their rodent group – that mightily bushy tail. Indeed, it is to this feature that they owe their name, ‘squirrel’ being derived from the Greek skiouros, which is a combination of two words, the first being skia, meaning ‘shade’, and the other being oura, meaning ‘tail’. So ‘squirrel’ ultimately comes from skiouros, and ‘shade-tail’ seems like an eminently suitable description for these little rodents, who can often be seen sitting on a branch and gnawing away on a tasty nut with their bushy tails curving up and over their backs.

Of course, this also explains where the red squirrel and grey squirrel get their scientific name from, with their genus name being Sciurus, the Latinised form of skiouros. But it is the second part of their scientific names – that is, their respective species names – that reveal that one of them is an invader, and invite us to find out more about these rodent relatives, as well as the battle between them and how it began.

Well, the native red squirrel’s scientific name is Sciurus vulgaris, with vulgaris simply meaning ‘common’. But this is quite ironic in many respects as some think that the red squirrel may have gone extinct not once but twice in Ireland.

For instance, it may have been present in the late Ice Age, suffered extinction, and then re-established itself on the island in the early Holocene (Holocene Epoch: 11,700 years ago–Present). But though it was plentiful enough during the Middle Ages that its pelts were exported, and this continued into the mid-1600s, in the 1700s this species suffered drastic decline as the forests which sustained it were felled – a process which persisted until the island was left with less than one per cent forest cover by the early twentieth century.

With such wholesale and relentless destruction of its habitat, this decline of the red squirrel deepened until by the end of the 1700s it is thought to have suffered extinction. But, of course, this was not the end of its story in Ireland. Not long after it had disappeared, efforts were made to re-establish red squirrels on the island, with captives from Britain released in at least ten different locations between the years 1815 and 1876. Interestingly, then, while the red squirrel as a species is considered a native mammal in Ireland, and has likely been present for thousands of years, its current representatives on the island actually have recent British ancestry, so the line between native and invader is not as clear as we might like to think.

In any case, despite the continuing destruction of forests in Ireland, the red squirrel somehow spread as the nineteenth century progressed, to the point that by the early twentieth century it had become re-established in every county on the island. But just as its prospects were starting to look sunny, a dark cloud appeared on the horizon in the form of what would become its nemesis, the grey squirrel.

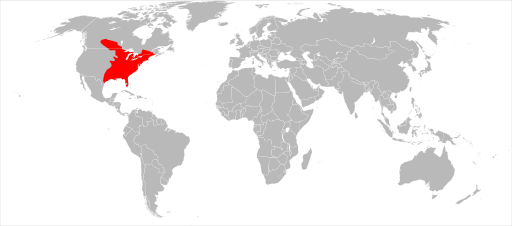

From whence the grey squirrel came is revealed by its scientific name, Sciurus carolinensis, with carolinensis simply meaning ‘of Carolina’, referring to the US state which provided the specimens on which the first scientific description of this species was based in 1788. The grey squirrel, then, is native to North America, being widespread in the broadleaf forests of the eastern part of the continent, from the Gulf of Mexico in the south to the Great Lakes in the north, and from the eastern boundary of the vast grasslands of the Great Plains in the west to the Atlantic coast in the east.

And, left to its own devices, here the grey squirrel would have remained, but human actions have resulted in it now being found in locations far beyond its natural range. For instance, it is now widespread in some western parts of North America too, while its human-aided dispersal has also seen it cross wide oceans to other continents, now being found in South Africa and parts of Europe, and it was even introduced to Australia in the late nineteenth century.

But though the grey squirrel never managed to establish itself in Australia and all of the introduced populations have now disappeared, its success as an immigrant on other continents has been dramatic. For example, in a 2015 article in The Irish Times, the journalist and naturalist Michael Viney noted the astonishing speed with which the grey squirrel spread across parts of northern Italy after the introduction of just a handful of individuals only around 70 years ago. And it all started with a gift.

In 1948, the US ambassador brought four grey squirrels to Italy as a present, but from the few came many – a testament to the reproductive powers of rodents – and by 2010 the descendants of the original quartet had become a free-ranging army, these invaders having conquered over 2,000 square kilometres of Piedmont, that large region of northwestern Italy of which Turin is the capital. And having borders with France and Switzerland, it is now feared that Piedmont’s grey squirrels could spread to these countries in the next few decades and, eventually, advance across great swathes of Eurasia.

This story of Italy’s grey squirrels is instructive as regards the grey squirrel invasion of Ireland as it too started with a gift, albeit one bestowed almost 40 years earlier. Most of the grey squirrels in Ireland today can trace their lines back to 1911, when the Duke of Buckingham brought eight grey squirrels over from England as a wedding present for the daughter of the Earl of Granard at Castle Forbes in Co. Longford. And from this location, just east of the Shannon, the grey squirrels spread, and are now found in many counties in the north, east, and south of the island.

The success of this invader in Irish lands has been a great challenge to the lives of the native red squirrels on the island who seem to be outgunned in many respects. Grey squirrels are not only larger than their native competitors but more aggressive and omnivorous. For instance, greys and reds both like to eat hazelnuts, but greys can also take full advantage of the nutrition provided by acorns, a food source which, although also availed of by reds, is not easily digested by them and is, in fact, somewhat toxic to their systems. On top of this, because greys spend more of their time than reds foraging on the ground, they can often raid the food caches squirrelled away by the reds in the late summer and autumn when food is plentiful.

But as well as engaging in forms of open combat or stealth war with the reds, the grey invaders also seem to prosecute a form of biological warfare. In Piedmont in Italy, for example, in over half the area that greys have conquered, the reds have been exterminated, largely due to the spread by greys of the squirrel-pox virus which does not seem to affect them too much but is utterly devastating to reds, who can swiftly die of symptoms resembling those of the rabbit disease myxomatosis. This squirrel-pox has recently appeared in Ireland and is yet one more weapon in the grey invaders’ arsenal in their struggle with the native reds, known from other areas to facilitate a much quicker replacement.

Faced with such seemingly overwhelming odds, it is hard to see how Ireland’s native reds could hold out against such a powerful invader, and yet the red squirrel continues to endure and in some places is even experiencing a resurgence. It seems the greys do not have all the advantages after all, and the reds’ resistance struggle is being aided by everything from the assistance of other native mammals to the very geography of the island itself.

As Michael Viney notes in his 2015 article, an island-wide survey conducted in 2007 showed that the greys had advanced on many fronts since they first began their invasion in 1911, a century later being found in Co. Donegal in the very northwest of the island, across every county in the North, and all along the east coast down as far as Co. Waterford in the southeast. In the south, the greys had made it as far as Co. Limerick and were threatening the border of Co. Cork. However, this survey also revealed that greys had become rare in large parts of the centre of the island, in the counties of Cavan, Laois, and Offaly, where reds had begun to thrive again.

Later research seemed to confirm that the reds’ recovery was likely tied to that of another native species on the island – the pine marten. In the 9,000 square kilometres in the centre of the island that the reds had once again become common and widespread, pine martens were plentiful too.

Like the red squirrels, pine martens had suffered greatly from the deforestation of the island from the seventeenth century onwards, but in the 1940s they were still found in many locations. From this time onwards, though, it became one of the rarest mammals on the island, mostly found in the mid-west from Limerick to Sligo, and especially in the Burren, while also maintaining a presence in a few isolated spots in Waterford and Meath. Lately, though, the pine marten has been on the advance once more, and the most recent squirrel survey noted that in 2012 it had been sighted in every county except Derry.

This survey also found that reds, although still under pressure from greys in many places, are now found in every county on the island. It turns out that a number of those features that give grey squirrels an advantage over reds when they compete with each other directly are the very same ones that make them more vulnerable when predatory pine martens enter the equation.

For instance, because they spend more time on the ground foraging, grey squirrels appear to be far more prone to predation by pine martens than reds are, which are rarely attacked by pine martens and have a greater ability to escape in the trees, their smaller and lighter bodies meaning they can retreat to the very extremities of branches.

On top this – as mentioned in yet another article from Michael Viney, this time from December 2018 – a recent study has also found that grey squirrels are more vulnerable to attack from the pine marten as they are less sensitive to this predator's scent than are red squirrels.

This readvance of the pine martens has also aided the reds’ resistance struggle in that it has lessened the burden on the Shannon as the last line of defence in halting an invasion by greys of the west of Ireland. Greys have, in fact, been observed a number of times on the west bank of the Shannon, and it is possible for them to make a crossing due to the branches of trees on both banks reaching over to meet one another in several places along the river, forming arboreal bridges. However, thus far such sporadic crossings have not resulted in any large-scale invasion of the lands west of the Shannon and the reds of the west can still live in peace.

So, just as with many human invasions of Ireland, in the epic squirrel struggle the Shannon has acted as a natural barrier between natives and invaders. The red squirrels have also been aided by the rise of other natives on the island who are unwittingly stemming the flow of invading greys across the land. Thus, though the grey squirrels have unleashed a torrent of misery on the native red squirrels since they were first gifted a place amongst Ireland’s mammals, the reds have so far weathered the storm. The skies may be grey but there are rays of hope yet shining through from a scarlet sun – the reds may still survive this alien invasion.